Although she would never, of course, confess it aloud, Clara was not looking forward to the end of the war. She could not imagine returning to her old, ornamental existence. Sometimes, as she spent her days tending to the weakened and dying, bandaging bloody stumps and carrying buckets of the foulest slop imaginable, she flashed upon a memory of her old self, that petulant heiress whom she now pitied, despised, even hated for her narrow world view and lack of purpose. Was it only three years since she first stood at the steps of this once-grand antebellum mansion, wondering what she had let herself in for? She was an entirely different creature now, so physically altered she doubted even her sisters would recognize her — or would want to claim her as their own.

Clara had many reasons for not wanting to go home.

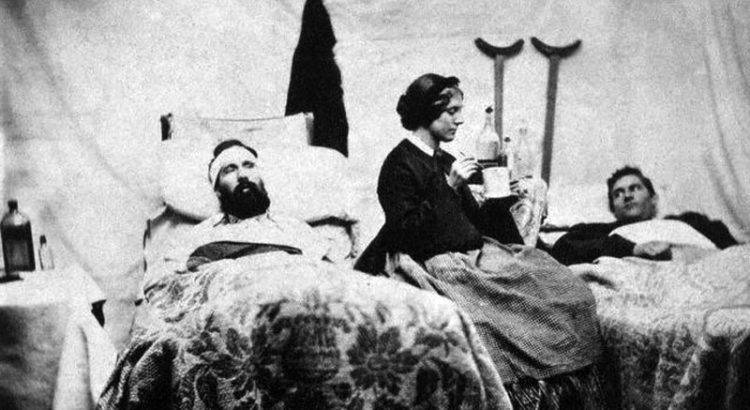

Her ward, five adjacent bedrooms on the second floor, and the wounded soldiers who passed through it, meant everything to her. She performed a vital function here as night nurse, in perpetual motion, soothing feverish brows and clutching icy fingers, carrying bowls of clean water and bloody slop. Her willowy arms had become chunky with muscle and the fine skin on her hands had wrinkled with the work. Her glossy black curls, with no one to wash and style them, had proven impractical and been cropped short. She had even changed her name. In this place, ‘Clarissa’ was too grand and prissy, so she now went by the quieter ‘Clara’.

On the rare occasions she glanced in a mirror, she felt her eyes were her most altered feature. Before, they had been twinkling shallows. Now, they were cloudy pools, reflective of the ravages she had witnessed, the wreckage of flesh, the punctured lungs, the blasted eyes, the gangrene-blackened limbs. In three years there was no war injury that she hadn’t seen — or smelled. In the operation room she could shut her eyes when the rising pile of mangled limbs disturbed her, but there was no way to remove herself from the stench; the rusty blood, the sickly-sweet maggots, the putrid fruit of the soiled sheets. Her shift ended as the sun rose, but even when she returned to the nurses’ dorm on the top floor, stripped off her bloodstained pinafore, the stench clung to the hollows in her skin and drifted up from underneath her nightgown. There was no escaping it, even in her dreams.

Not that she dreamed much. What was there to dream of, when the ward was her whole world?

Once, she’d been Clarissa Lowell of Richmond, fizzy debutante, about-to-be-affianced to Denton Moss, the pale, frowning embodiment of every single one of her mother’s social climbing aspirations. Early in the war, however, Denton and his father embarked almost immediately upon the RMS Scotia for Liverpool, citing urgent business in Europe. The Mosses bid the Lowells a fond farewell and promised to return in a few months. Clarissa, who had been looking forward to the parties and gifts generated by marriage to a uniformed beau, hid her disappointment, at least in public. In a private letter to a friend, she described Denton’s departure as “the worst travail I shall ever have to bear. How humiliating to be affianced to a coward, when all the other young men around me are bold and glorious heroes off to war.”

She had no idea.

As the war churned into its second year, mothers of the conscripted dead started to point at her crossing the street. Despite the fact that her engagement to Denton had never been made official, they referred to her as “the coward’s girl”, and shunned her whole family’s company. Clarissa burned under the injustice of the accusations, especially as, after a single, tepid letter, Denton had failed to stay in touch. She was no coward. She could see only one way to right the wrong Denton had done the Lowells and decided to enlist in his place.

The militia would not have her, so she petitioned for a position as a nurse. This necessitated a great deal of letter writing, and waiting in offices, and, in the end, subterfuge. She scraped back her hair into the severest of buns, perched a pair of spectacles on her nose, borrowed a dress two sizes too big, invented an absent husband and added ten years to her age before finally impressing an officer with her overall sobriety and lack of flightiness. She was on the next train out.

During those first weeks at The Poplars, Clarissa thought she had landed in Hell. The cartloads of broken men, dumped on any available horizontal surface, writhing in an agony of mud and blood, seemed the embodiment of lost souls. As she was listed as “married”, Matron assigned her to washing the incomers, assuming that she had at least a passing acquaintance with the naked male form. Clarissa did not, and what she saw the first time she lifted a sheet made her faint clean away. One of the young Negro women, Ida, took pity on the horrified debutante and educated her on the finer points of male anatomy, what a woman could touch and what it was best avoided. Clarissa soon learned.

Over the months, Clarissa and Ida became, if not friends, something more than the nodding acquaintance acknowledged between the rest of the lady nurses and the enslaved women who had been requisitioned along with the house. Clarissa had been taught never to forget a kindness, regardless of the color of the hand that offered it. At first, Ida was irritated by the girl’s patronizing chatter and rarely uttered a word in exchange. Then, gradually, as their disparate life experiences converged into one long ward round of dirt and death, they found a common thread. Anxious to avoid comment on the fatal wounds of the men they bandaged and bathed, but unable to shake the somber mood, they told ghost stories as they went from bed to bed.

Clarissa waxed eloquent on monks, highwaymen and drowned maidens. Ida countered with a wayward hunter who fell down a porcupine hole and found himself in the country of the dead. Between them, they wove a nightly narrative from the points familiar and strange in their cultures, an ongoing, intercontinental saga that put Scheherzade to shame. Some of the men listened in silence, some contributed their own episodes, and others assisted with an exaggerated shriek upon a punchline. Matron fretted that her girls were too morbid, but the dying found comfort in the ongoing discussion of their terminal destination. Clarissa and Ida’s stories offered hope of light up ahead.

And so, by the spring of 1864, Clarissa Lowell, once of Richmond, was gone and in her place stood Clara, Angel of the Night. She rarely saw the sun so her skin was unearthly pale, enhancing the darkness in her eyes. Nonetheless, there was nothing but light in her soul. She bore witness to the passing of so many desperate men from substance to shadow that an almost supernatural purpose shone within her.

And then, she disappeared.

There was much confusion in the house the day it happened. Typhoid raged around the wards. Every hour, more wagons laden with the wounded trundled up the drive. The orderlies were hard pressed to keep up with the flow, loading the live bodies in and the dead ones out. When Nurse Clara didn’t report for duty that evening it was just one more problem Matron was unable to deal with. Ida went to look for her friend, but her bed had not been slept in. No one recalled seeing her at meals during the day. But there was no time, and no able-bodied volunteers, to mount a search.

Three days later, Matron reported Clara missing to the Surgeon-In-Charge and he recorded the fact in dispatches. There was nothing more to be done. The men in Clara’s ward fretted over the loss of their storytelling Angel, but soon the individuals who had been nursed by her died or moved on. After six weeks only Ida carried the memory of Clara’s chiaroscuro face with her, turning it over and over in her mind, unable to explain her abrupt departure. Ida suspected Clara had been taken against her will, but had no clue who would do such a terrible thing, or if they would strike again.

One sunny afternoon, while pegging linens out to dry, she confessed her fears to her Aunt Issey, who worked in the kitchen and gave occasional help with the laundry. Issey disliked and mistrusted all the lady nurses and couldn’t understand Ida’s concern.

“If one of them was taken, means one of us is safe,” she said. “’Tis chilling to think, though, even with all the dyin’ here daily, the house takes its tithe. Twenty dead soldiers a day ain’t enough. Still needs a girl.”

Ida didn’t understand what her aunt meant that day. However, as the war ended, and the years passed, and Ida had daughters of her own, she understood that it was wise to keep them away from The Poplars. It broke her heart to send them off to work in Richmond and Charlottesville, but she believed, the further away from the house, the better. And, every time she heard of another girl gone missing, she sent up a prayer for Clara, hoping that she hadn’t suffered too much.

One thought to “MISSING: Clarissa, 1864”