Y’all know what a phallic symbol is, right? A jutting representation of the male ego: the rod, blade, column, crane, rocket, gun, flagpole, or even the pen used to pay homage to the penis. Our cityscapes are littered with them, proud skyscrapers and spires thrusting into the pliant sky, proclaiming the upward intentions of their architects, testifying to the gargantuan wealth and ambition of their owners. Huge. Tremendous. The biggest and the best, always – until the next guy builds a bigger one in an endless race to the top(less towers of Ilium).

It’s impossible to live in the 21st century without being exposed to these monuments to patriarchy on a daily basis. As well as dominating our skylines, they abound in art, literature and popular culture. From poetry to comic books, phallic symbols are placed front and center in narratives. We’re so used to seeing them, we barely notice yet another superhero whose costume highlights his penile properties – throbbing gristle, veiny flesh, bulging tendons, smooth head, and, hello accoutrements! Thor’s Hammer, anyone? We’ve internalized the phallic symbol as integral to the way we navigate everyday experience.

When I was a student, I remember discussing Tennyson’s Mariana in one particular first-year seminar. Poor Mariana, trapped in her moated grange, with the most depressing view ever of broken sheds, moss-encrusted flowerpots, a black, sluggish stream and the “glooming flats” stretching as far as the eye could see. You can hardly blame her for such a woebegone refrain: “I am aweary, weary/I would that I were dead.”

The sole break on Mariana’s monotonous horizons comes in the form of – you guessed it – a perkily upstanding poplar tree. She’s mostly aware of it at night, when she’s abed, divested of her tight Victorian corsetry, and thinking of things forbidden in the daylight hours –

And ever when the moon was low,

And the shrill winds were up an’ away,

In the white curtain, to and fro,

She saw the gusty shadow sway.

But when the moon was very low,

And wild winds bound within their cell,

The shadow of the poplar fell

Upon her bed, across her brow.

So,” said our impeccably feminist tutor. “What do we think is going on here?”

Ha!” I said. “The poplar tree is a phallic symbol. Its falling shadow represents the oppression she feels from white cisgender heterosexual males (OK, so I’m paraphrasing. It was the 1980s) in both a sexual and intellectual capacity – it’s lying across her bed, representing her physical body, and her head, which is her mind.”

Boom.

I will never forget the delighted smile from my tutor that was the reward for this observation. I’m such a sucker for this type of rare, untrammeled approval that, as you are all well aware, I’ve transformed this single shining moment into a sweeping fiction, a place known as The Poplars where the Marianas of this world can grapple with their moat-induced misery, secure in the knowledge that the ever-ready wood chipper awaits any unruly or invasive trees.

I digress.

Years later, as a teacher myself, I trained students to see the phallic symbol in the text in front of them, to recognize its potency, comment, nail that A grade and move swiftly on. The patriarchy rewards fealty. It was only as a writer, working outside any hierarchy, immersed in the still-gaseous world I was creating, that I began to grope for another way of thinking. I didn’t want to erect my narrative out of protuberances, struts and frets. I wanted to use the female equivalent. But I didn’t know what that was.

I’m ashamed to say it took me a long time to discover the technical term for the opposite of phallic. It’s not commonly taught or used – we’re too distracted by the shadow falling across our beds and brows. I’d often seen femininity (and by extension female genitalia and sexuality) described in terms of absence, a hollow or void, a gaping ‘O’ beyond which lay darkness, something unfathomable, with neither tangible value nor any potency beyond the pull of mystery. Because women don’t have outward-thrusting protrusions, the reasoning goes, there is nothing there, therefore female symbols can therefore be spoken of only in the abstract, negated, as the antonym of phallic, a holdover from the days when men of science thought the vagina was just an inside out penis.

That has to be the greatest trick the patriarchy ever pulled, convincing the world that the feminine never really existed except in terms of not-male.

But, as any woman with a functional finger (and maybe a mirror) knows, there is something there. Something that is as solid and complicated and unique and specialized and textured and miraculous as a penis. There are external protrusions, flesh which engorges, muscles for the purpose of enjoyment and ejaculation. And there’s also a word to describe anything in art and nature that evokes the marvelous mechanisms of the human female genitalia: the yonic symbol.

Yonic symbol. Yonic symbol. Yonic symbol. It feels good to write it out loud. Yonic is from the Sanskrit, yoni, which describes the force of the goddess Shakti in Hinduism, an ancient religion which recognizes the need for balance between the male and female, and indeed that the female deserves a solid physical representation in art – stone yonis are found in temples all over India. The yoni represents birth, origin, source, and the creative impulse in nature.

Yonic symbols tend to be much older and more pervasive than phallic, reminders that goddess-worship, once so popular with our ancestors, might still be hard-wired into parts of our brain. Nature loves her some yonic design, from clam shells to pomegranates, the lotus flower to the rose. In architecture ancient and modern, cupolas and gateways evoke the female. In literature there’s the innermost cave, the tomb, the underground tunnel, the mountain spring, the Tarot’s cups and the actual Holy Grail.

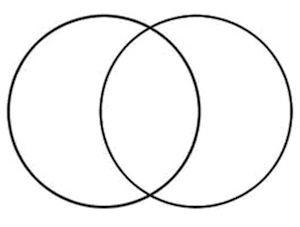

Then there’s the almighty Vesica Piscis:

This represents the universal moment of creation: two cells dividing. It represents your first moments as human being, exiting a birth passage between your mother’s thighs. It’s also the phases of the moon, the chalice, a major element of Gothic architecture, the Eye of Horus, a portal between worlds, the Pythagorean ‘measure of the fish’ that shows the intersection of the material with the supernatural, the basis of all polygons, the beginning of the Fibonacci and binary mathematical sequences.

Even though this symbol is far, far older than Christianity,that upstart religion chose to co-opt its power. The ‘fish bladder’ (Icthys) was used by early Christians to identify one another when they had to worship in secret. As the religion took hold, the Vesica Piscis was used as a way of framing images of Jesus and the Virgin Mary, and adorns walls, triptychs and windows in countless churches across Europe. The Sheela-na-gig figure was (before Victorian prudery decreed they all be torn down) a common sight carved into pre-Reformation Irish churches (see below). Her presence warded off evil, a nod perhaps to the enduring influence of the Mother Goddess, even after the come-lately Christians had built atop her shrine.

I probably don’t need to tell you that The Poplars is awash with yonic symbols, and that Poplars girls devote a great deal of time to their study, in sacred geometry, earth science, ancient history and literature classes. It’s all part of their unique education.

Take the yonic symbol away with you as a gift. Don’t worry that it sounds like a word emitted by a trust fund hippy recently returned from a totally authentic ashram experience, claim it as your own. Write it down somewhere safe. Start using it. Celebrate it. You’ll see yonic symbols everywhere, once the phallocentric blinkers have fallen from your eyes. And, whether you’re male or female, dear reader, once you see this symbol of female potency everywhere around you, you can start recognizing and utilizing the power of the goddess within yourself.