September is Ripper Season. Jack began the autumn of 1888 as a complete nobody and ended it as the most feared man in the United Kingdom. He materialized with the first mists but vanished before the winter frosts took hold, leaving an enduring mystery in his wake. To this day, people are still picking apart what he did, who he was, what it all meant. I’ve written about him before,as pop culture’s greatest boogeyman. 128 years after his crimes, he is as vivid in our collective consciousness as ever, the killer who rode the twist of his knife into history.

This September, however, I’m thinking about Jack’s women.

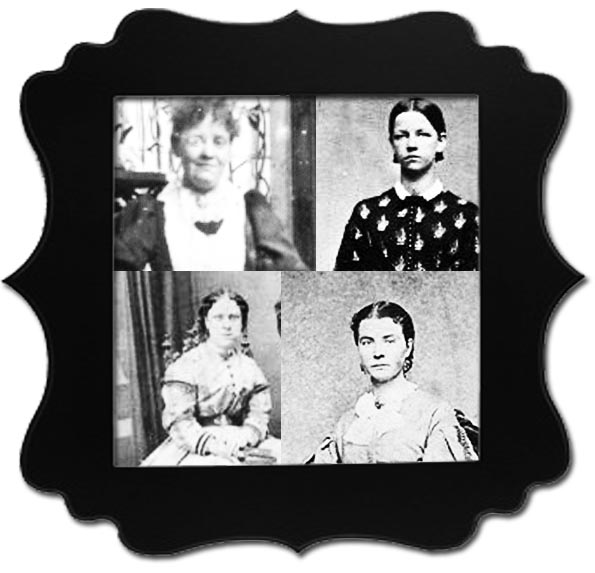

Over the years, much ink has been expended on Jack but his women, if they’re spoken of at all, are dismissed as mere pieces in his puzzle-making. The canonical five – Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly – dominate the narrative over the others who may or may not have fallen to Jack’s blade: ‘Fairy Fay’, Annie Millwood, Ada Wilson, Emma Smith, Martha Tabram, Annie Farmer, Rose Mylett, Elizabeth Jackson, Alice Mackenzie, Frances Coles and Carrie Brown. We only know their names today because Jack picked them, projected them onto the front pages and made them forever his. We don’t know why he selected these particular victims. Was he exacting a specific revenge, killing to order, or reacting against any random unfortunate who blundered up against his misogynistic fury?

Jack chose his targets from the very bottom of the social pile, women who had fallen almost as far as it was possible to fall. His September 1888 victims were diminutive brunettes in their mid-forties, impoverished, alcoholic, diseased. They lived the very definition of little lives, scurrying unremarked through Whitechapel, existing from one handful of halfpennies to the next.

43 year-old Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols fell hard and fast after July 1888, when she was fired from her job as a domestic servant for stealing – quite possibly the dress she was murdered in. She then bounced from workhouse to dosshouse, sometimes earning the few pennies required to sleep in a room with several other women, sometimes not. On the cold, wet night of August 30th she was thrown out of one of her regular spots, a dosshouse at 18 Thrawl St, because she had empty pockets. She swore she’d earn the price of a bed for the night and come straight back. A friend, Emily Holland, chanced upon her, rolling drunk, at 2.30am, and reported Polly as saying, “I’ve had my doss money three times today and spent it” – presumably on liquor, and who can blame her for wanting to numb her misery? So Polly stood in the rain, hoping for passing trade, a soldier or sailor who would lift her skirts and have his satisfaction for the threepence she needed to be warm and dry. Emily walked on, the last person to see Polly alive.

Jack’s next pick, 47 year-old Annie Chapman, had had an unhappy summer too, caught in a complicated, volatile relationship with a bricklayer’s mate, Edward Stanley. He switched his attentions between Annie and one Eliza Cooper. In August the women came to blows over Stanley, leaving Annie with a nasty black eye and other bruises. Once, Annie had a husband and children, and earned her way with crochet-work and selling flowers. By 1888, however, her husband was dead and Annie was destitute, like Mary Ann working the back alleys for the price of a night in a dosshouse when she couldn’t find a bed with Stanley. She was half-starved, lungs riddled with tuberculosis, and possibly syphilitic. That first full week of September, Annie was feeling ill, enough to procure medication, but she had to keep working – or else sleep rough. In the early hours of September 8th, she left her regular quarters, Crossingham’s, and headed off into the night to earn enough pennies to lay claim to her usual spot, ‘Bed 29’. At some time around 5.30 a.m. that morning, she met Jack.

In the early 1870s, Elizabeth Stride (known as ‘Long Liz’) ran a coffee shop in Poplar (!) with her husband. By that September however, she was a 45 year-old widow, with no teeth in her lower jaw, prone to bouts of rambunctious drunkenness that made her a frequent visitor to the Thames Magistrate Court. She went back and forth to the home of Michael Kidney, laborer, but they argued a lot and she would take refuge in a lodging house at 32 Flower and Dean Street. She eked out a living cleaning rooms, sewing, begging for alms from the Swedish Church (she was born in Sweden) and occasional prostitution. On the night of September 30th, 1888 she supposedly had sixpence when she went out, so turning tricks might not have been her initial intent. It appears that may have been the way her evening progressed. Witnesses place her with several different men over the course of the next few hours before her final, fatal assignation, shortly after midnight.

That same night, 46 year-old Catherine Eddowes was on her way home from a few hours spent in the drunk tank at Bishopsgate Police Station. Along with her partner, John Kelly, she had recently returned from a summer spent hop-picking in Kent. Unlike Jack’s other women, Eddowes was in a relatively stable relationship (with Kelly) and was not known to be a habitual drunk or a prostitute. She was also considered intelligent and well-educated by those who knew her, and once earned her way writing and publishing ‘gallows ballads’, cheap one-sheets commemorating lurid crimes of the day. Kelly waved her off to visit her daughter at around 2 p.m. that Saturday afternoon, and no one knows what happened between then and 8 p.m., when a blackout drunk Catherine was found sprawled on the pavement (and surrounded by a crowd) on Aldgate High Street. Two local bobbies hauled her to her feet, dragged her off to Bishopsgate and tossed her in a cell to sober up. She had fully regained her senses by 1 a.m., when she exited the police station with a cheery “Goodnight, old cock” to the desk sergeant. Her mutilated corpse was discovered 45 minutes later.

If it weren’t for Jack, we wouldn’t know even these sparse details about the tenuous existence of these women. The murder investigation, as it always does, pulled back the curtain on their hard, hard daily round, surviving moment to moment in the grimmest of Victorian slum conditions, their lives almost as brutal as their deaths. In their younger, prettier years, they had some options – marriage, children, flower-selling, domestic service – but by September 1888 their luck, in so many ways, had run out.

Yet Jack still saw something in these broken women that infuriated him beyond reason. He didn’t just kill, he butchered them, ripping them apart in the ultimate act of desecration. He took them, unconsenting, and made them into monstrosities with a hand cruder than Victor Frankenstein’s. He stripped them of agency and made them his creatures for all time, posing them in a manner that has become their permanent memorial, thanks to the autopsy reports and mortuary photographs. Could Jack have ever guessed that in 2016 his handiwork would be available the world over at the click of a button? I suspect he would like that.

This September, I wanted to look past the images from the slab, and remember Polly, Annie, Kate and Liz as living the struggle, loved by friends and families, capable of laughter and good cheer despite their poverty, part of a close knit community that watched each other’s backs. All of them were quickly identified after death. Only Annie was buried in a pauper’s grave (the police and relatives wanted to do it in the utmost secrecy). Thousands thronged the streets for Kate’s funeral. Jack’s women would, I’m sure, have preferred to live out their little lives in penniless obscurity, rather than being dragged screaming into a maniac’s myth-making. They deserved so much more than that. They deserved – as do older, poor, disenfranchised women everywhere, still – so much more than Jack.

Ever since Cain slew Abel, murder – especially of the ‘most foul’ variety – has provided us with a route map through human history. It’s a long and winding road from the filthy back alleys of Victorian Whitechapel to the verdant green of The Poplars’ valley, but I’ve always known there was a connection to follow. How could there not be? What that connection is, well… you’ll have to wait until Book 2 to find out (and it maybe has something to do with the bad doctor, Francis Tumblety). However, you’ll get some inkling of how deep and complicated the links are by reading about Nellie Forbs, who disappeared from The Poplars in December, 1888.