The history of racial violence in the USA is usually framed in terms of the suffering of young black men, from George Stinney (executed, aged 14 in 1944 for a double murder he did not commit) to Emmett Till (lynched and mutilated, also aged 14 in 1955 for flirting with a white woman) to John Earl Reese (shot dead, aged 16, from a speeding car for the crime of dancing in a café, also in 1955) to the roll call of the present day, Freddie Gray, Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin et al, et al.

The history of racial violence in the USA is usually framed in terms of the suffering of young black men, from George Stinney (executed, aged 14 in 1944 for a double murder he did not commit) to Emmett Till (lynched and mutilated, also aged 14 in 1955 for flirting with a white woman) to John Earl Reese (shot dead, aged 16, from a speeding car for the crime of dancing in a café, also in 1955) to the roll call of the present day, Freddie Gray, Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin et al, et al.

Less attention, as always, has been paid to the crimes against black women. Although they were not lynched and murdered by white men in quite the same numbers as their menfolk, black women suffered longer, and more silently, as the victims of rape. From the era of slavery into the late twentieth century, white men used black women as sexual punching bags with impunity, denying them the most basic of human rights, agency over your own body. As well as one-off attacks there was ongoing debasement. During slavery, this might turn into a legal arrangement (via the much-debated Plaçage system) and in the Jim Crow years it devolved into so-called “paramour rights”. Whatever it was called in polite company, society condoned it, and, should the victims have the temerity to complain, law enforcement looked the other way.

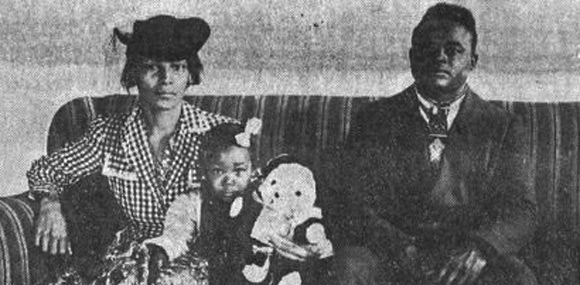

On September 3, 1944, 24 year-old Recy Taylor, a devout Christian wife and mother of a baby girl, was walking home from a Sunday evening service at the Rock Hill Holiness Church, in Abbeville, Alabama. Seven young white men drove past in their car, looking for kicks. They abducted her at gunpoint and gang-raped her. Afterwards, they left her bleeding and blindfolded at the edge of town. They warned her if she ever told a soul about what had happened, they would return and kill her.

Then they drove away. It’s doubtful a single one of them believed there would ever be any consequences for the terrible thing they had done.

Recy, despite her ordeal, found the strength to report the crime to local police. There had been a witness to the abduction – another church-going lady, Fannie Daniel – and the two women between them were able to describe the green Chevrolet and the men riding in it. In a small town like Abbeville, this should have made arrests (and conviction) easy. It was the kind of place where everyone knew everyone – heck, they were even related. The Deputy who took Recy’s statement shared her last name (Corbitt), suggesting they could both trace their ancestry back to the same local slaveowner, who had counted Recy’s great-great-great-grandparents among his possessions and treated them as such. The poison went back generations.

Rather than prosecuting the rapists, however, the local Deputies began to construct an elaborate cover-up. They accepted the young men’s denials and alibis. They ignored Recy’s good character. They accused her of getting into some kind of fight with local boys and lying to hide the fact she had attacked one of them. Recy, supported by her family, refused to drop her complaint – despite the verbal threats and the Molotov cocktails tossed onto her porch.

Determined to get her case heard outside the local web of corruption, Recy called the NAACP branch office in Montgomery and told them her story. They sent a young activist named Rosa Parks to investigate further. Abbeville law enforcement was not amused and physically threw her out of town. In response, Parks launched a national campaign, the Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor, which attracted widespread support. It eventually forced Governor Sparks to launch a second trial – although, predictably enough (the jury was all-white, all male), none of the defendants were found guilty.

“Though the mills of God grind slowly, yet they grind exceeding small” – Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Although she finally got them into a courtroom, Recy’s rapists were never brought to justice. However, her bravery in standing up and pointing the finger, her refusal to view her violation as anything but a crime, played a pivotal part in the struggle for equal rights. She inspired other women to the same kind of resistance and played an important part in changing perceptions. We’ll never know how many young white men read about her campaign in the newspapers and thought a little more carefully about the consequences of their actions, and, as a result, how many more young black women walked home from church in safety. In March 2011, Alabama issued a formal state apology to Recy for failing to prosecute her rapists in 1944.

Not so far away, in Virginia that same year, another young black woman was walking home one night and was accosted by young white men out on the prowl. They were all trespassers – locals largely ignored the signs put up by The Poplars authorities, and felt entitled to take the same shortcut they and their ancestors had been taking for centuries. What happened next is still the subject of ongoing debate.