Eudora Kemp was a Poplars nobody – until that final, tragic afternoon when she seared her name on School history. She was plain, stolid, undistinguished academically or artistically, and lacking in the type of family connections that might make up such a shortfall in charisma. Additionally, she was cursed by frequent waves of pimples that marched across her cheeks – yet another reason why she was considered untouchable within the clear-complected caste system of the School.

In the spring of 1919, one of the younger housemaids, Bessie Evans, took pity on Eudora and her skin condition. Bessie recommended twice-daily cups of nettle tea and the frequent application of an acrid solution from a small,stoppered bottle. This triggered an immediate improvement in the doomed girl’s acne, and all was well for several weeks until one of Eudora’s dorm-mates sniffed the contents of the precious bottle and identified the main ingredient as urine. Of course, the information that Eudora Kemp was smearing ‘Negro piss’ all over her blotchy face swept through the school like measles. By lunchtime she was entirely humiliated.

Eudora cornered the too-helpful Bessie late that afternoon, in a remote spot north of Cecilia’s Walk. Eudora had somehow acquired a horsewhip and set to flogging her victim with a viciousness born of shattered self-esteem. The housemaid’s terrified shrieks brought a trio of young gardeners running. They dragged the flailing Miss Kemp to the horse trough and tossed her in. In the heat of the moment, they felt cold water submersion was the swiftest way of subduing her until the headmistress, Dr. Corstairs, could be brought to the scene. They were only too aware of the usual penalties imposed on black boys who laid hands on a white girl, but they thought, under the circumstances, they might be forgiven.

Sobbing, soaked to the skin, but no longer kicking and clawing at anyone within reach, Eudora was removed to the infirmary where she was sedated, pending further inquiry. Dr. Corstairs heard one half of the story from a distraught and bloodied Bessie, as she was having her wounds cleaned and dressed by Matron. She then heard another quarter of it from the girls in Eudora’s dorm, who did their absolute best to absolve themselves of any blame in the matter whatsoever. Dr. Corstairs agreed to wait until the following morning to interview Eudora herself, to permit the traumatized girl to regain her composure. In a letter to her sister she regretted her decision:

“Why didn’t I sit down with Eudora there and then to get to the very bottom of the matter? There were so many questions only she could answer! Why wasn’t she in class? Where did she unearth such a fearsome instrument of torture? How did she persuade Bessie to abandon her duties and follow her so far from the main School building? And, most importantly, what possessed her to wield the whip with such force that it bit through Bessie’s uniform and flayed the skin from her spine? Eudora was such a nonentity, a girl you barely noticed passing in the hall, completely lacking in spirit or grit. The very Devil himself must have taken hold of her.”

Whatever Eudora might have to say in her own defense, her permanent — and hurried — exit from The Poplars was inevitable. Dr. Corstairs telephoned the Kemps and asked them to withdraw their daughter voluntarily. Mr. and Mrs. Kemp set out from Baltimore with all haste, but when they arrived at The Poplars the following morning they found the place in uproar. Eudora had vanished overnight.

Publicly, Dr. Corstairs reassured everyone that the contrite Eudora had simply fled the scene of her crimes and would return of her own accord, probably before Tea. Privately, she feared that news of the schoolgirl’s determination with a whip had reached the ears of the surrounding community, and inflamed the old, bad blood between the inhabitants of The Poplars and the local sharecroppers. Very privately, in another letter to her sister, she remembered the stories about the girls who’d gone missing from The Poplars in the years since the Civil War, before dismissing them as superstitious nonsense. “I believe Eudora has run away of her own accord,” she wrote. “What would anyone want with such a miserable, homely creature?”

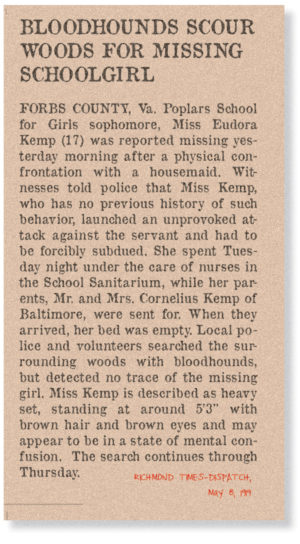

When another day passed and there was still no sign of Eudora, the Kemps called the local police, who in turn alerted every newspaperman in the Commonwealth. The headlines trumpeted “SCHOOLGIRL RUNS AMOK, RUNS AWAY” across the state, and the scandal was reported on every front page from the Richmond-Times Dispatch to The Baltimore American.

The local Klansmen read the story with interest and drew their own conclusions. Their retaliation against Bessie and the three youths who’d rescued her from Eudora was immediate and absolute.

The bodies were discovered just after dawn, swinging gently from the ancient oak in Rafney’s Acre. They were cut down within the hour and wheeled away on garden carts. The coroner recorded the deaths as suicide without attending the scene or performing an autopsy. Again, from a letter between Dr. Corstairs and her sister:

There is no arguing with these blank-faced men. Outside The Poplars’ gates I am just another hysterical woman, without power or authority, all too easily ignored to suit their ends. I am the only one who will speak for the victims, and my voice goes unheard in this wretched moral wilderness. The Chaplain has advised me to take what crumbs of comfort I can from the swiftness and secrecy of the incident. At least they weren’t burned, he reminds me. Or mutilated in front of a crowd. At least it happened in the darkest hours of a moonless night when all the other girls lay fast asleep…”

Consumed by the need for some kind of justice, Dr. Corstairs ordered the antiquated tree chopped down the very next day, obliterating the scene of the crime. But erasing every physical trace of the incident wasn’t enough. Several copies of a souvenir postcard of the lynching surfaced, showing the distinctive blasted oak, its strange fruit, and, in the middle distance, there was no mistaking The Poplars, wreathed in early morning mist. The heinous deed, photographed by person or persons unknown, was commemorated for the record for all time, much to Dr. Corstairs’ frustration and shame. Again, from correspondence with her sister:

That d——ed photograph! It must have been taken moments before I arrived. Which means, of course, the murderers must have tipped off the photographer before they even began proceedings. He must have been setting up his equipment even as they tightened the noose around those poor boys’ necks, and hit the shutter as soon as the light was right. The image is crystal clear and very artfully framed. Then he packed up and slipped off into the forest as I was hurrying to the scene of the crime. As complicit as any of the killers! I suspect one of the Gilbey boys. They’re familiar enough with the property, the fathers and sons of that family have been coming and going with their cameras since The Poplars was the Forbs’ family home. To think they’re turning a profit from that vile picture, selling it across the county! I would end their association with us as a penalty, but Gilbey Senior is such a craftsman, and there are no other skilled photographers for miles and miles…”

Dr. Corstairs was subsequently axed by the Board of Governors, who accused her of stirring up trouble with local dignitaries. The new regime, headed by Miss Apsley, took the drastic step of firing the black maids employed inside the house and replacing them with recent graduates of an all-white industrial school in Richmond. This act did not improve relations with the community and would have stark repercussions over the next decade.

Amid all this upheaval, the search for Eudora Kemp was quietly abandoned. Her family never heard from her again.