In 1912, around sixty girls slept on the second and third floors of the main house, in small dormitories of four to six beds apiece. Gloria Atkinson shared a bedroom with three other ninth-graders — Gertrude Mortimer, Gladys Portnoy and Jemima Delreaux. They were a tight-knit group known, for obvious reasons, as the ‘Gee-Gees’. Around 3 a.m of the morning of November 2 (a Saturday), girls in the adjacent bedrooms, at the west end of the second floor, were roused from sleep by a toxic, choking, burning smell. They rushed out into the main corridor to discover oily smoke roiling from the Gee-Gees’ dorm. After a moment or two of schoolgirl fluttering, a couple of the braver girls busted down the door. Rather than the expected conflagration, they found a grisly set of human remains in Gloria’s bed. The head and torso had been completely obliterated by fire. Two bare legs, the skin pink, pristine, untouched from the upper thigh downwards, lay atop the sheets.

Hysteria ensued. Within seconds, the entire School was awakened by the commotion. Police and firefighters were called from the nearby town — even though there was no longer any blaze to extinguish. Alerted by the clanging bells on Main St., the eldest Gilbey daughter, Estella, grabbed her notebook and pen and roused her brother, Theolonius, yelling at him to fetch his camera. Even in her late teens, Estella had a nose for news, and she had Theo gunning the engine of their father’s car within ten minutes flat, just in time to follow the fire truck to The Poplars.

Theo and Estella were familiar with the interior of the main house from accompanying their father on photographic business. They went straight to the scene of the crime, via the back stairs, before anyone was aware of their presence. They escaped in an equally clandestine fashion. Thanks to the iconic photograph Theo took of what remained of poor Gloria, and the copy Estella filed later that morning, the sensational story was picked up by newspapers from coast to coast: SCHOOLGIRL SPONTANEOUSLY COMBUSTS.

Perhaps it was the Gilbey siblings’ inexperience, or their ingrained sense of discretion where Poplars girls were concerned, but their initial coverage did not mention the other residents of Gloria’s dorm. Estella obtained a brief statement from one of the girls who had discovered the body, and confirmed the particulars with the fire chief, but at the time she didn’t realize there were three potential eyewitnesses. She wasn’t alone in her omission. It seemed no one paid any attention to the whereabouts of the other three Gees. It took a couple of hours of chaos before it became apparent to everyone that Jemima, Gladys and Gertie were missing, and not simply milling around in the confusion.

The rumors spread rapidly that Gloria’s immolation was the result of a Hallowtide prank gone wrong. Opinion was divided. The girls assumed the surviving three Gees had either fled the scene of their crime, to be concealed and protected by their families forthwith, or they had been instantly disgraced and expelled. Dr. Corstairs let the gossip bubble for a week or so, then diverted the girls’ attention by announcing a grand surprise, a Winter Ball, the first such event to be held at The Poplars in more than a decade. Her ruse worked: the Gee-Gees were quickly forgotten.

In the wider world, the story also faded from the headlines, filed under “Macabre Curiosity”. Estella Gilbey, on the other hand, buoyed by the thrill of seeing her byline in print nationally, became steadily more high profile as a reporter, chasing scoops in New York City throughout the 1920s, then restlessly roaming the West in search of stories during the Depression. She never forgot her first big break, however, especially as the incident was referenced when any other case of SHC was reported — usually via a direct quotation from her original reporting.

As she grew older, and angrier, she regretted not asking more questions that night at The Poplars. She berated her younger self for focusing solely on the action and ignoring the context. She did her best to correct the error with a dogged investigation, especially once she learned there were three other girls in Gloria’s room that night. She tracked down former students and quizzed them on their memories of the incident. Many of them confessed to her that they had found the whole affair very strange, but felt they were forbidden to speak of it, even years after they graduated. She plagued now-retired teachers with questions. She flirted her way into the police files and obtained a copy of their somewhat baffled initial report.

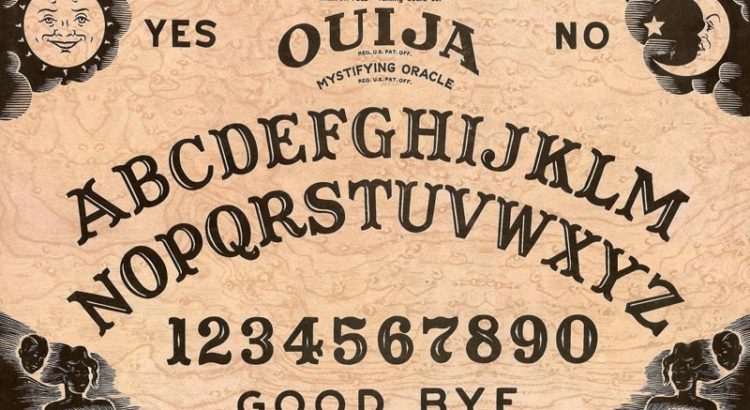

Painstakingly, she pieced together at least some of the background detail. Divination was a hot topic in Poplars dorms during the fall of 1912. One of the seniors, Alice Rowe, acquired a ’Ouija Wonderful Talking Board’ over the summer and it became her clique’s favorite form of evening entertainment. A couple of their number became very skilled at guiding the planchette without seeming to do so, and were adept at spelling out the exact name a girl wanted to hear when asking about the identity of her future husband. The seniors regarded their sessions as a harmless parlor game, especially as the answers to their questions always seemed to come out the way they wanted.

Within a few weeks they grew bored of the never-ending affirmatives and the Ouija board was stashed in the back of a storage closet on the second floor. However, when Gertie Mortimer picked it up and carried it back to the Gee-Gees’ dorm, eager to emulate the older students, things took a decidedly darker turn.

The Gees were, as a group, quite blue-stocking in inclination, and had no interest in future husbands or children. Their curiosity was much more spiritualistic in nature and they wanted to commune with the dead, in particular, one of Jemima’s English cousins, Charles Edgar, who had perished aboard the R.M.S. Titanic in April of that year. Seventeen year-old Charles had been a dreamy, poetical type, always very kind to Jemima, and she felt, out of all her acquaintance among the recently deceased, he would make the most benign spirit guide. So the Gees set about contacting him. Jemima asked the questions, Gladys and Gertie operated the board, and Gloria sat ready with a pen to write down the letters of each word as they appeared. They worked with the planchette for a couple of nights before getting any decipherable results. Then, on October 28th, a new force seemed to guide the girls’ hands, and spelled out its first identifiable words: C-O-L-D-S-O-C-O-L-D. Gloria transcribed them, dutifully, into a notebook, which was stored along with the Ouija board in a cardboard box. Guilt-ridden, Alice Rowe rushed into the dorm and grabbed this box amid the confusion of 11/2/12. She was terrified she, and her harmless parlor game, might be blamed for the tragedy. Estella managed to track Alice down almost a decade later and obtained the notebook from her.

Unfortunately, the notebook revealed little about the Gees’ last evening. Gloria only wrote down dates and answers, not the questions. The spirit communiqués ran as follows:

10/28/12

C-O-L-D-S-O-C-O-L-D

B-R-I-G-H-T-S-T-A-R

W-A-I-T-I-N-G

P-R-A-Y-F-O-R-M-E

T-E-L-L-U-N-C-L-E

G-O-N-E

10/29/12

T-E-L-L-U-N-C-L-E

M-E-R-C-Y

C-H-A-R-L-E-S-E-D-G-A-R

L-E-T-T-E-R-L-E-T-T-E-R-L-O-S-T

W-A-I-T

10/30/12

B-R-I-G-H-T-S-T-A-R

M-O-R-I

F-O-R-G-O-T

M-O-R-I-M-O-R-I-M-O-R-T-E-M

C-A-R-P-E-N-O-C-T-E-M

S-T-A-Y-A-W-A-Y

G-O-N-O-W

P-L-E-A-S-E-G-O

NO NO NO

Things took a different tone on Halloween:

H-E-L-P-M-E

R-E-W-A-R-D

Y-O-U

Y-O-U

Y-O-U

O-P-E-N

E-D-G-A-R-N-O-T-C-H-A-R

S-T-O-P-S-T-O-P-S-T-O-P

E-N-D-L-E-S-S

Only one message was listed for 11/1/12:

L-U-K-E-2-3-2-4

Then, on the fateful night of 11/2/12, the Day of The Dead —

N-O-W

M-I-N-E

Y-O-U-R

A-L-L

T-I-M-E

Estella puzzled over the words for hours, but could make no sense of them. Her instinct for a story never failed her, and all her senses tingled that there was so much more to this one than she could guess. As far from solving the mystery as ever, she filed the notebook away with the rest of the material she had collected over the years.

Another decade passed before she picked up some new information. In the mid-1930s, Estella’s peregrinations took her through Franklin, Tennessee, which just happened to be Jemima Delreaux’s hometown. She made a few discreet inquiries about the family, who still lived quietly in the neighborhood, and was regaled with a most peculiar story.

One evening about five years previously, the recently widowed Mrs. Delreaux was about to sit down to dinner when there came a knock at the door. She answered it to discover a shivering teenage girl, hair matted to her head with mud and twigs, garbed in a ragged nightdress. The grubby creature shrieked ‘Mama! Mama!’ and attempted to embrace her, only to be dragged off by a manservant. Mrs. Delreaux called the Sheriff, who took the hysterical girl away.

Wrapped, sobbing, in a blanket at the local police station, the girl claimed she was Jemima Delreaux, that she had been taken from her bed at school “maybe two days ago” to an underground chamber, where she was bound and blindfolded. After much struggling, she managed to free herself, and claw her way through roots and tunnels to the surface. She was surprised to recognize some Franklin landmarks, and managed to find her way to the Delreaux residence, where she fully expected her overjoyed Mama and Papa to welcome her with open arms. She admitted that at first, she thought she had the wrong house because the woman who answered the door looked “so old”, but then she insisted that she was no trespasser, that she had every right to enter her family home.

The detective who took the girl’s statement decided he was dealing with an impostor, who had heard the sad tale of the real Jemima and thought she could exploit the grieving parents, not realizing that the tragedy had occurred many years previously. It was all too easy to disprove her claim: Jemima Delreaux’s birth was registered as December 15th, 1898. She would have been in her early thirties. The girl sitting in the holding cell could not have been more than fourteen. He felt there was no need to press charges – in such hard times who can blame a hungry girl for trying? – and turned her out into the street with a warning.

Intrigued, Estella followed every avenue of inquiry, but could find no further record of what became of the girl after that. Diary entries show she continued to investigate and theorize about the case until her death in 1970. Strangely, there is no mention of the Gees in her memoir, One Curious Dame, published posthumously — perhaps these passages were excised by the publisher?