Aloysius Gilbey, gentleman scientist, was a contemporary of Edgar Forbs, although he was educated overseas, in Germany. The two men shared an interest in chemistry, although Aloysius was concerned that his friend focused on the esoteric rather than the scientific. Throughout the 1840s they visited one another regularly, sharing their thoughts on the latest papers from the Chemical Society or the Royal College of Chemistry from England.

Aloysius also assisted Edgar in his quest to concoct the perfect Mercury chloride solution to keep his syphilis symptoms at bay. For his part, Aloysius observed the progress of the disease in Edgar with a cool scientific detachment, making notes in his journal about Edgar’s state of physical and mental health. He ordered a textbook with beautifully drawn chancres and pockmarks, annotated it, and gave it to Edgar as a birthday present. There was an argument between the two men when the book disappeared.

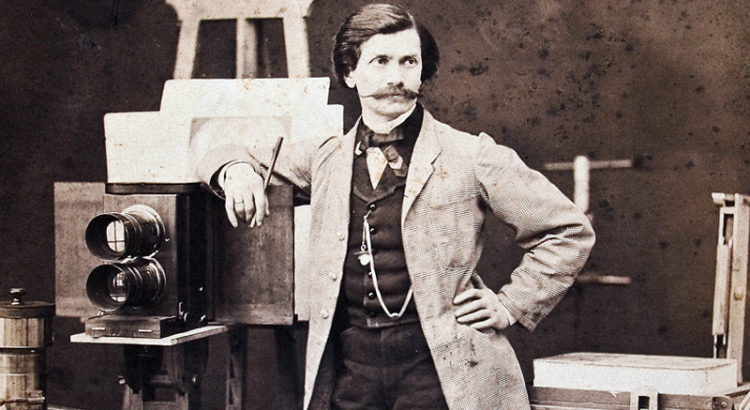

When Mathilde died in 1853, Aloysius persuaded Edgar and Mercy to sit with her for a final family portrait, and indulge his new hobby of daguerrotyping. Aloysius brought his teenage son, James, to The Poplars to help with the session. Aged just fifteen, James was showing a true aptitude for both the art and science of photography, though Aloysius was usually the one to take credit for the work.

Aloysius propped Mathilde’s corpse in a chair, and photographed her next to her daughter, Mercy and stepson, Edgar. This was a fairly routine set-up for a portrait photographer of this era — at least the dead could be trusted to remain still enough to accommodate the long exposure times. Aloysius was most concerned with keeping the irritable Mercy motionless for long enough to capture a series of images, but James was focused on other details. From his diary entry:

Seeing the three of them together shook me to my bones. Mercy and Edgar, who are half-siblings, are remarkably similar in appearance and share the same curious feline-amber eyes. Mercy bears little or no resemblance to her mother, dead or alive…

…After we had successfully exposed six daguerrotype plates, Father and the others left me to create a final, solo memorial of Mathilde. In truth, I prefer working in solitude with a completely immobile subject…

…I had been alone with the late Mistress Forbs no more than a moment or two when I heard a child’s cough from behind one of the drapes. I pulled it aside to reveal a young girl — with the face of a monster. Her skull was hideously misshapen, bumps and hollows jumbled into the wrong places. Her skin bubbled over her cheeks in tumorous contusions. However her eyes, glittering deep in their uneven sockets, were instantly recognizable. Whoever the child was, she was closely related to the Forbs family. Therefore I could not risk crying out or demonstrating my revulsion in any way.

She pleaded with me to be allowed to pose, just once, with the deceased lady. I had two unused plates left in my case, and saw no harm in it. Indeed, I thought a clear image of such a freakish creature might command a high price from the right buyer, a discreet collector of medical curiosities, perhaps? The child did, however, beg me to keep the image entirely secret until I could find the opportunity to return it to her as a keepsake. She also bade me not to breathe a word about her presence in the room, or the fact that she had spoken to me. “Papa will be furious,” she said.

James kept his promise. He kept the finished daguerrotype locked away in a vault. It was the first exhibit in what would come to be known as the Gilbey private collection, a treasure trove of images capturing the grotesque, sordid, violent and criminal sides of Forbs County life from 1853 until the mid-twentieth century. These images remained a closely guarded secret within the Gilbey family until Daniel Gilbey decided to donate the collection to the UVA archive in 2011.

Although the Gilbey collection is not listed in any public catalogue, nor are any of the images online, interested parties may apply on an individual basis to view specific items.